It all started at the age of seven when a small circular patch appeared on the top of my head. It’s strange with vitiligo because you never really know what the trigger is. In my case, it kicked in when my grandad passed away. I think a lot of my vitiligo outbreaks are due to emotional trauma.

From then till the age of 11, it started to break out in lots of different places. It covered my hands, my feet and then my knees and face. By year seven, I was covered in white patches.

My mum started applying makeup on my face when I was ten. She was trying to protect me, like you do with any of your children. But you know, later in life, it was more of a detriment than it was any kind of protection.

I felt like I appeared quite confident at school. When I put that makeup on, it was almost like there was nothing there. Secondary school can be horrible, and kids can be horrible. But I can’t sit here and say that I was bullied through my school life because that wasn’t the case. I felt like I carried myself quite well and I had good friends. The teachers were supportive too.

The impact it had on me was more on a social level. I didn’t go on school trips because I was worried about taking my makeup off in front of people. I didn’t have sleepovers at friends’ houses.

I never used to wipe my face during PE, so I would just constantly sweat all the time, and the makeup would run down my shirt. That’s when I would feel most conscious of it.

If I could turn back time now, I wish I never wore makeup. I was an 11-year-old putting makeup on every morning all the way up until I left school. I didn’t stop wearing makeup until I was 27, and I’m 35 years old now.

I’ve worn makeup throughout my entire school life, throughout most of my working life. Waking up every morning and sitting down in the mirror for 45 to 50 minutes, applying it, making sure that it looks alright, and then putting foundation on top of it. It was tedious, and I hated it.

I’ve got two little boys now, and they’ve got a chance of getting vitiligo because I’ve got second and third cousins who have it. If my boys do end up getting it, then I will treat it completely differently to the way that my parents handled it when I was younger.

I come from a Turkish Cypriot culture and, to be fair, when I was diagnosed there wasn’t a lot of information out there about vitiligo. I think there was a language barrier, but they were never inquisitive. When we went to the doctor, they would never ask questions. They just wanted a solution. But there was no solution. There was no cure. I think they found that hard to take, which is why they opted for the makeup. They thought, “Okay, let’s just cover it all up.”

I feel like my wife saved me. Amy and I started secondary school together, but we didn’t start going out until I was 15 years old. We’re still together now. We’re married, we’ve got two kids and it’s been an amazing journey.

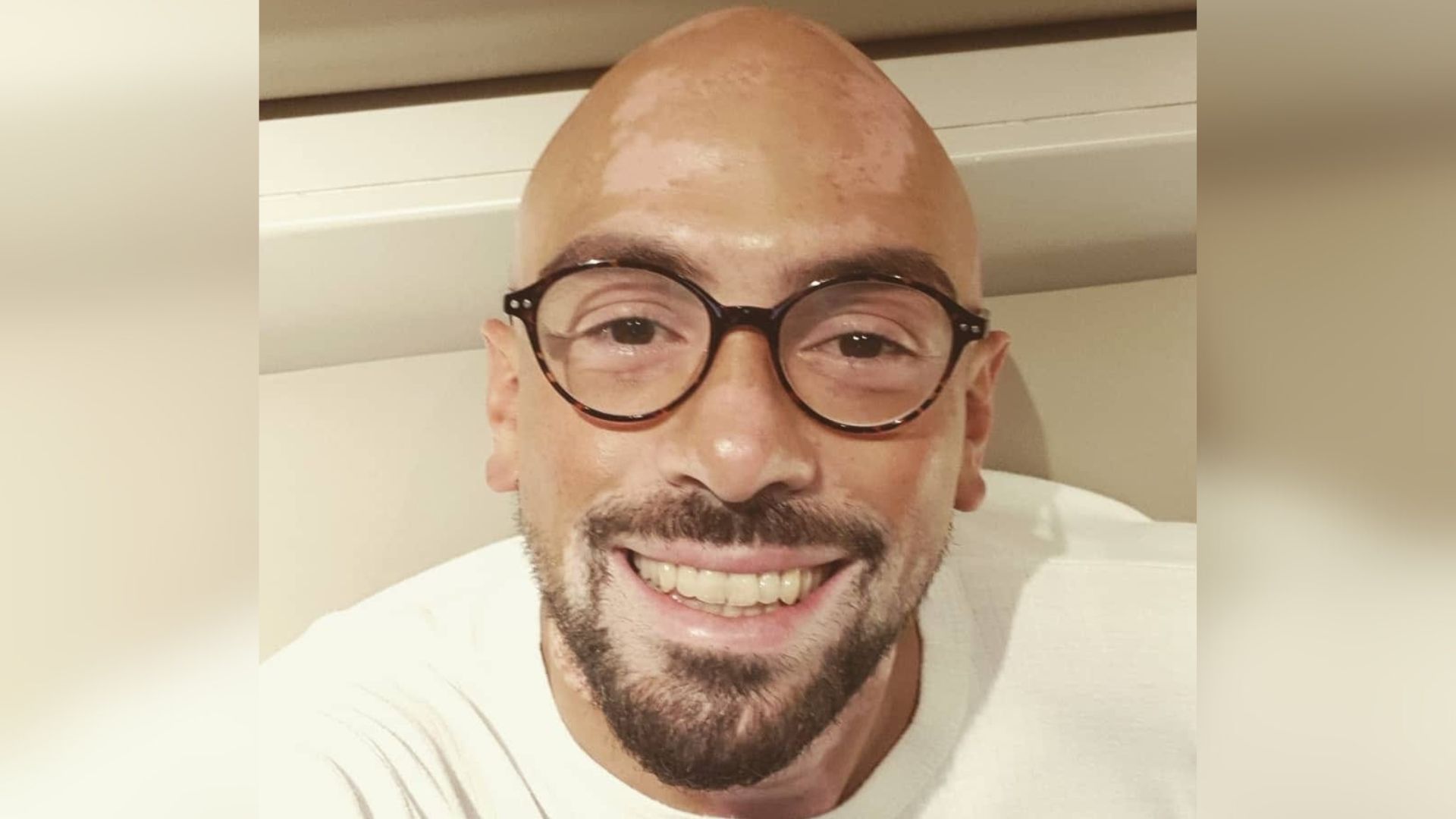

Elj credits his wife Amy with helping build his confidence

She was the catalyst for change in me. She was the first person who I opened up to about vitiligo. She was the first person who saw me with without makeup. She was the first person who gave me confidence. Amy tried for a long time to get me to not wear any makeup. Slowly, I would do things like not wear makeup on weekends when I was just with her. That was kind of a slow burner.

We decided to get married in Jamaica when we were 27. We went there when I was 21, and it was probably the most uncomfortable experience in my life. I was wearing my makeup all the time we were there, and I was constantly sweating as a result. But we decided to get married in Jamaica because that was our first big holiday together.

I remember thinking that I didn’t want to look back at our wedding photos and say to myself, “God, I’m sweating in that picture.” It started to really stress me out because I think I was ready to let go of wearing makeup at that point, but at the same time, it’s probably the one day in your life when you want to look your best.

That’s when a really minor comment changed my whole perception of the situation. Amy went for dinner with Charlie, one of her friends, and they’d discussed my reservations about wearing makeup at the wedding.

She told me that Charlie said, “Does Elj realise that people are looking at him because he is a man that wears make up, not because of his skin?”

I’ve never heard someone outside my circle talk about it like that, and it really did trigger something in my head. The following Monday I was sitting in the spare room and getting ready to put my makeup on. I remember staring in the mirror and thinking to myself, “I don’t want to do this anymore.” I threw the makeup in the bin and walked out of the house.

And that was it. I’ve never looked back since to be honest. It was probably one of the best decisions I’ve ever made in my life.

No one really said anything at work apart from one of my close friends who gave me a huge hug and said, “I’m really proud of you.”

But people are curious. It’s only now that I’ve started talking about it that people have actually reached out to me and said, “You know, I remember the day you came in with no makeup.”

I’d never been in situations where people have sat down and asked me about it before. But now I want people to ask me questions because I want to educate people about vitiligo and how it affects people.

Last year, my employers developed this initiative at work called London Voices for members of the team to share life experiences. I was the first one to volunteer myself to speak. I think there was about 75 people in the room, and 75 people dialed in from home.

I went through my whole journey from the day I was diagnosed up until where I am today. At first the thought of speaking up was quite daunting. Now I find that the feeling is quite empowering. The feedback I have had from colleagues, ex colleagues, family and friends has been really overwhelming, quite draining to be honest. I didn’t realise my story would resonate with so many people. Since then, I’ve written a piece for the Independent about my journey with vitiligo too.

By sharing my story, I hope to help others feel empowered and understood. Vitiligo is still perceived as a hidden disorder, and my aim is to breakdown those barriers.